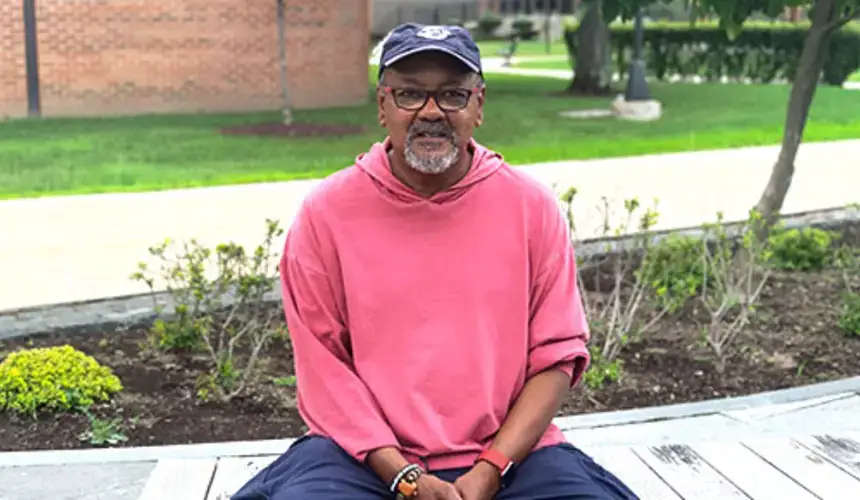

For Mack Culpepper, there’s only one thing better than coaching: training future coaches.

During his 45 years as a coach – primarily for varsity girls’ basketball at Franklin and Schenevus central schools and AAU girls' teams at the Oneonta Boys and Girls Club – Culpepper has made a lasting impact on hundreds of local athletes, teaching not just basketball but also life lessons on perseverance, sportsmanship and fairness.

For the past 10 years as an assistant professor in the Department of Sport and Exercise Sciences, he has continued to make an impact by passing his life experience on to the next generation of coaches.

“This is what I always wanted to do”

After earning two- and four-year degrees in law enforcement, Culpepper had a change of heart and decided he wanted to be a teacher. He spent a year with Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA), moved to Oneonta in 1976 to earn a master’s in education at SUNY Oneonta, and landed a job in the Financial Aid Office in 1979. In 2011, Culpepper retired from full-time work after a 32-year career at SUNY Oneonta – 19 years as a financial aid counselor and 13 years in Student Accounts – and then began a second career teaching coaching classes.

“I love it,” he says. “This is what I always wanted to do.”

His favorite class is Philosophy, Principles and Organization of Athletics in Education, a key requirement for students pursuing a minor in Athletic Coaching or earning New York State Coaching Certification.

“I tell my students: Know your craft. Be the best teaching coach out there. Because I don’t care what plays you run. If you don’t have what I call the ABCS, the 123s, plays don’t mean anything. You’ve gotta have the fundamentals.”

“I’ll put my toes right up to the line”

Known as a “tough coach,” Culpepper says he enjoys “pushing kids to do things they don’t want to do or think they can't do. I heard somewhere this belief that athletes only give you 50 percent. Coaches have to draw out the other 50 percent.”

He has a strong philosophy about winning the “right” way. “I know the rules, I also make sure my players know the rules, and I’ll be honest: I’ll put my toes right up to the line, but I won’t cross it.”

Culpepper has stayed in touch with many of his former students and players and says the most rewarding part of being a coach is “the friendships that come out of it.”

When he was battling Stage 3 colon cancer in 2017, a parent from his AAU team coordinated a rotation of hot meals delivered to him and his family every Wednesday after his chemotherapy treatments. "And that doesn't happen unless the team wants it to happen," he says.

"All I want to do is reach one kid”

Culpepper grew up in Canastota, NY, “a small Italian village in Central New York where everybody knew everybody,” with eight adopted and foster brothers and sisters.

“A lot of my coaching philosophy and teaching came from my mom,” he recalls, sharing some of the time-tested “Culpepperisms” he has reinforced with his players and students: “Know right from wrong. Don’t lie. Be correct in what you say. And fight like a dog for fairness.”

Known as the “class clown” in junior high and high school, Culpepper struggled at the community college level. He will never forget the mentor who saw his potential and convinced the college to give him another chance when he was in danger of flunking out.” I woke up out of my coma before it was too late. I had to study. I’m not brilliant,” he recalls, joking, “Except in sports. As my mom used to say, ‘I don’t know how you can remember what Micky Mantle did last week but you can’t remember this algebra formula.’”

Now, Culpepper pays it forward as a mentor to Oneonta students who are struggling. “I see a little of myself in some of these kids. I am not going to let them fail. If they’re like me, slow learners, I call on them in class, I work with them, and I cut them some slack. Knock on wood, I haven’t been wrong about anybody I’ve given a chance to.”

He finds the ability to make a difference, one student at a time, more gratifying than even the most dramatic, come-from-behind win on the basketball court. “When I was young and worked sports camps, I wanted to reach everyone,” he says. “Now, being older and wiser, all I want to do is reach and make a difference in one kid.”